“If gratitude is something we can practice on purpose… what happens when we practice purpose itself?” ~ Richard D’Ambrosio

The average man will spend more time on Thanksgiving consuming the day’s abundance than contributing to it. I’m sorry. The facts are what they are. We men are, on average, more self-valuing and selfish than women, the result of a combination of biology (higher testosterone levels) and socialization.

Men have the power to counter the effects of this combination through intentional and repetitive acts of giving to others. The human brain is wired that way, and when you understand its neurochemical mechanics, you open up a brighter and more fulfilling world.

My Thanksgiving of 2012 makes me certain of that.

I woke up the morning of October 30 in my Hudson Valley home to learn that Hurricane Sandy had flooded New York City’s streets, tunnels and subway lines, while downing trees everywhere and cutting power all over the city.

There were reports of dozens of fatalities and concerns were spreading that the breadth of the destruction would leave whole communities to live in brutal conditions for months.

I had been laid off a year earlier and wasn’t getting many interview offers. The constant stream of rejections were hollowing out my manhood. I was my family’s sole breadwinner and had grown up taught to believe that a man measured his worth by how well he provided for his family.

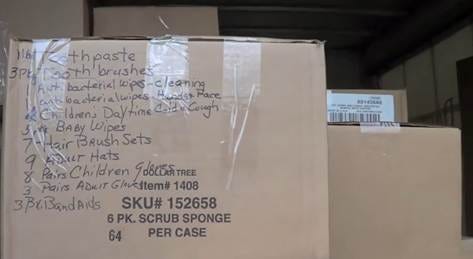

At the time, I was a very active member of my Catholic parish, St. Patrick’s in Highland Mills, NY. So when our religious ed director arranged for us to collect and donate food and water…

… children’s goods and clothing, to a sister parish on Staten Island, and a nearby neighborhood, I pitched in.

The November 10th drive was a huge success. (Watch the video here.)

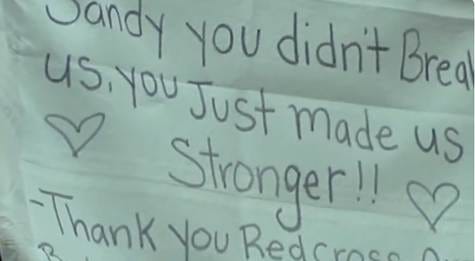

I was so touched by the decency of my fellow parishioners and the gratitude of the recipients of our gifts. I started making plans to volunteer again.

This time I would work with Occupy Sandy, a grassroots organization that had jumped in to meet the immediate needs of tens of thousands of newly homeless, filling the gaps that FEMA, the Red Cross and other organizations simply didn’t have the speed to serve.

A few days later, a friend of mine and I were at Occupy Sandy’s central aid distribution center located in a large downtown Brooklyn church.

We unloaded trucks, organized a wide assortment of donations — including food, clothing, generators — and loaded trucks delivering aid to communities in the worst affected areas.

That afternoon, we canvassed Coney Island, trying to reach elderly shut-ins living in apartment buildings that had no electricity, heat or elevators.

That visceral shift from “I’m useless right now” to “I am needed” lifted my unemployed, non-providing spirit. My heart was cracked open, emptied physically but full spiritually.

My then 16-year-old daughter wanted to follow in my footsteps and asked to volunteer with me the day before Thanksgiving. I had already decided that after seeing the devastation firsthand, it would be hard for me, someone who loved Thanksgiving more than any other holiday, to look forward to celebrating that year.

So I planned with my family to go with my daughter, then stay behind to work at a church cooking and preparing meals for thousands on Thanksgiving Day. It would be the first time in my life that I would not be celebrating Thanksgiving with at least one family member.

At sunrise Thanksgiving morning, I headed down to the foot of the Verrazano Bridge, arriving at the church around 6:30. It was already abuzz.

A group of professional chefs were firing up stovetops and ovens in the church’s industrial kitchen, while thousands of pounds of ingredients stacked throughout the main church hall waited to be transformed into thousands of Thanksgiving blessings.

That day was an eight-hour dopamine high. The main chef organizing everything took me on as his second-in-command.

He handed me orders based on what was needed to enter the kitchen next, and I worked with the rest of the team keeping this amazing assembly line humming.

Everything, from the smell of roasting turkeys, skillet cooked shrimp and vegetables, the sight of people from all walks of life doing the humble, quiet, joyful work of chopping, ladling, carrying and packaging trays, made me feel more at home than any family Thanksgiving table I had ever sat at.

As the sun began to set outside the church, and the last meals were packed up in autos and trucks, and on their way, the volunteers, most of us total strangers until that day, began to hug each other.

Some of us introduced ourselves for the first time, teary-eyed and overcome by the magnitude of what we had shared that day.

It was the best Thanksgiving of my life — I think because it was both mine and not mine at all. This is the lesson I think more men need to learn.

Our brains are wired for connection and altruism. Moments like what I experienced flood our brains with our natural feel-good drugs — dopamine and oxytocin — that are the perfect antidote for men big on self-valuing and low on selflessness, warmth and emotional awareness.

Thanksgiving 2012 lit up a new default configuration — agency in service and a useful tolerance for discomfort (the November cold, and missing my favorite holiday).

Purpose dragged my emotional life into the room before my default masculine personality had a chance to talk me out of it.

As you approach this wonderful day of abundance and this season of giving, let me leave you with five ways you can step into gratitude as a new or enhanced default masculinity:

Trade one hour of consumption for one hour of contribution.

All it takes is asking: “What can I do to help?”

Involve the next generation.

If you are a father or father figure, invite a child to serve alongside you. Let them see you in the kitchen, or in the muck, not just on the couch.

Use your “male” traits for connection, not escape.

Men are risk takers. Overcome your lack of knowledge about a task and volunteer anyway — with a heart open to screwing up and learning.

Host with your hands and your words.

If you have a home to gather in, take responsibility for some of the load: cooking, cleanup, or making sure the quieter people are seen and thanked.

Ask one question that costs you nothing and gives someone everything.

To a relative, neighbor, or stranger: “What are you carrying this year?” and listen. This is how high-armor men practice dropping the shield a little.

I hope this Thanksgiving is one that cracks open your heart in a new and unexpected way that helps you feel that rush of giving a part of yourself to others.

To you and yours, a very Happy and Thankful Day.