“Well I just heard… the news today. It seems my life is going to change…”

Creed lead singer Scott Stapp had just learned he was going to be a father for the first time when he wrote the 1999 song “Arms Wide Open.”

Stapp has lived a troubled life. In one interview, he said he was beaten as a child. He also said he was diagnosed as bipolar, and has attempted suicide twice. His first wife charged him with domestic violence, charges she later dropped.

In the lyrics of this power ballad, Stapp acknowledges to his unborn son how he might not be the best person to teach his child how to live a brighter life than he had chosen, a life with greater promise:

“Well, I don't know… if I'm ready… to be the man I have to be.”

The central image of the song is a man trying to live with his arms stretched open wide in acceptance of himself AND a world that affords greater happiness to those brave enough to be vulnerable.

In the music video, Stapp descends into a dark, subterranean place, goes through a baptism of sorts in a cave of water, and emerges into the sunlight. You see hints of something very familiar to Christians: Jesus, crucified and resurrected.

Whether you consider yourself religious or Christian, there’s a lot we can learn about masculinity from Stapp’s lyrics and Jesus’ last hours according to the Gospel of Luke.

Chapter 23 in Luke recounts the story of Jesus being brought before Pilate, the Roman governor of Judea. We witness Jesus’ trial and sentencing, his torture, and eventually his death. Throughout the chapter, Jesus is the docile sacrificial lamb, slain just as alluded to in some of the Old Testament scriptures (as interpreted by Christians).

The masculine myth, disrupted

Many people who call themselves Christian today don’t like this portrayal of Jesus, the lamb led to slaughter. They like the tough Jesus, the dominant, stoic one. They like the guy who flipped over the money changers’ tables in the temple.

These Christians are totally down with the man up Jesus version played by Jim Caviezel in Mel Gibson’s 2004 The Passion of the Christ, bloodied but determined, despite the centurions’ relentless and cruel punishment.

It’s almost as if these modern day Christians forget Luke’s 22 gospel chapters leading up to The Passion.

You know, like the chapter where Jesus told the disciples to stop interfering with the parents who brought their children to Jesus to be blessed [Luke 18:15-17]. Or how about the Jesus in Luke 22:19-27, who washed the disciples’ feet?

They seem to have forgotten how Jesus wept alone in Gethsemane the night before he was crucified [Luke 22:39-46], fearful of the pain and suffering he would endure the next day. He asked God to save him from this fate.

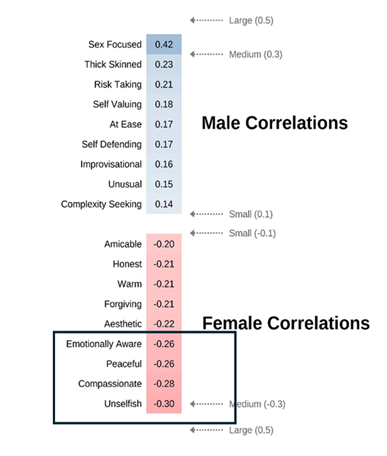

What we know from all four gospels is that Jesus probably would have scored high on the feminine end of the ClearerThinking.org Gender Continuum Test.

Could any man have been more unselfish than the one who sacrificed his very life for his family, friends and total strangers? Jesus’ compassion and emotional awareness are unrivaled. Throughout his life, Christ fulfilled the label Prince of Peace, even telling Simon Peter to sheath his sword when the high priest’s guards came to arrest him.

Jesus challenged his enemies with questions, not weapons. He broke bread with outcasts, and dined with betrayers. He forgave his friends for abandoning him. And he never let suffering make him bitter. In the Gospel of Luke [23:26-43], as Jesus is being crucified, he calls out: “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.”

Jesus is the clearest expression of mindful masculinity I’ve ever encountered. It was by studying him, accumulating shelves of gospel commentaries, study guides and biblical textbooks that I remained a Catholic and a Christian long after the Church lost me.

Reclaiming strength through love

For too many men, strength is found in the absence of feeling. Over the last three or four decades, many authors and leaders of a mythopoetic men’s movement have tried to convince men that crossing our arms and closing ourselves off makes us more masculine.

They say that living with arms wide open means you might be:

hurt, because vulnerability invites risk.

disappointed, because forgiveness doesn’t guarantee reciprocation.

misunderstood, since gentleness often is mistaken for weakness.

What they don’t tell men is that living with arms wide open means:

creating space for return, especially for those who have abandoned us, but may have had a change of heart.

modeling a masculinity that heals, instead of harms.

grounding ourselves in self-awareness, so we learn which crosses are ours to bear, and which aren’t.

Mindful masculinity isn’t about being soft. It’s about being strong enough to stay open.

“With arms wide open under the sunlight

Welcome to this place, I'll show you everything

With arms wide open, now everything has changed

I'll show you love, I'll show you everything.”

This kind of masculinity looks like…

the man who leans into the discomfort of hard conversations.

the father who apologizes to his son after yelling at him, showing that strength can kneel.

the manager who gives the employee a second chance, because they remember needing one too.

the son who doesn’t let his toxic upbringing determine his worth or his behavior.

the man who listens more than he speaks, and speaks with clarity when it matters.

It looks like arms — tattooed, wrinkled, bruised — held wide open.

The Apostles’ masculine creed

The “Arms Wide Open” lyrics that resonate the most for me are these:

“If I had just one wish, only one demand I hope he's not like me, I hope he understands That he can take this life and hold it by the hand And he can greet the world with arms wide open.”

Lots of men go through this process of self discovery when confronted with the prospect that if they don’t change, they might fulfill the verses in Exodus 20 and 34 — translated colloquially as: “The sins of the fathers, become the sins of the sons.”

I hear hints of Exodus in a quote often attributed to Frederick Douglass: "It is easier to build strong children than to repair broken men."

Whether Douglass said this or not, the sentiment rings true.

A baby is a blank canvas. Fathers can build their child’s spirit up through love and compassion, or destroy it with anger, selfishness, stoicism and self-valuing.

As hundreds of millions celebrate Easter Sunday today, this author, a Buddhist father of three, will say his own prayer for every man struggling to live his life with arms wide open. I will pray for salvation with a new gospel – one of mindfulness, empathy, curiosity, and a courage made of vulnerability.

To all who celebrate – Happy Easter.